By Shahid Sattar | Sarah Javaid

Pakistan’s implicit export strategy isn’t goods – it’s people. And the strategy continues. In a recent statement, the finance minister announced plans to train one million youth annually, priming them for jobs in Gulf economies, especially Saudi Arabia. The rationale? Pakistan’s skilled workers will power “Saudi Arabia’s transformation”, while the remittances they send back will help rescue Pakistan’s own faltering economy.

This policy begs three critical questions: Have we become a nation that equips its youth to build other economies? Has exporting people taken priority over exporting products? And most importantly, have we embraced remittances as our default economic strategy?

For decades, Pakistan has leaned on remittances as a current account stabilizer. But let’s not mistake a dependence model for strategy. These dollar inflows aren’t the result of industrial upgrades or strategic reforms. They stem from the steady outflow of our manpower, intellect, and talent.

According to the World Migration Report 2024, Pakistan ranks 6th globally in remittance inflows, receiving $30.2 billion – nearly 9% of GDP in FY24. In March 2025, monthly remittance inflows crossed $4 billion for the first time in the country’s history. If current trends hold, FY25 could close with an all-time high of $36 billion.

The statistics surrounding outward migration are staggering. In 2024, the number of Pakistanis leaving for overseas jobs jumped 69% from 2020. Nearly half of them were classified as ‘skilled labor,’ according to the Bureau of Emigration and Overseas Employment. With the finance minister’s latest announcement, it’s clear: emigration is no longer market-driven – it has evolved into a national strategy.

Had the country prioritized skills training to boost domestic productivity and promoted a conducive job market, much of this brain drain could have been redirected toward wealth generation through productive activities.

The irony is that the impact stretches beyond the brain drain. Ample research reveals that while remittances boost household income and consumption, they also create a cycle of dependency, diverting demand and resources toward non-tradable goods. This drives up prices in non-tradable sectors and undermines export competitiveness – classic symptoms of Dutch disease.

While economists continue to debate the extent of this effect, Pakistan’s case is hard to ignore. Our analysis shows a clear negative correlation between rising remittances and exports-to-GDP, coupled with elevated consumption and imports. Meanwhile, human development indicators remain dismally low, suggesting that the influx of dollars has not translated into long-term socio-economic prosperity.

While this article may not exhaust every channel through which remittances affect the economy, it definitely makes one thing clear: remittances, while taken as short-term buffers in Pakistan, are no substitute for a serious growth strategy.

Remittances vs Human Development:

Approximately 727,000 Pakistanis left the country in 2024, and by March 2025, an additional 172,000 had followed. As a result, Pakistan is now the 7th largest source of international migration globally.

To place this in a broader context, over the past 50 years, more than 14 million Pakistanis have emigrated, 57% of whom were skilled professionals, including engineers, doctors, nurses, accountants, and technicians. Ironically, these are the very skills vital to the growth of Pakistan’s export-oriented manufacturing and services sectors. The result is a steadily shrinking pool of skilled professionals at home.

While emigration – having doubled over the past two decades – has led to a sharp rise in remittances (up 240% in dollar terms), the social payoff remains conspicuously absent, as the country’s HDI indicates a regressive trend in human development.

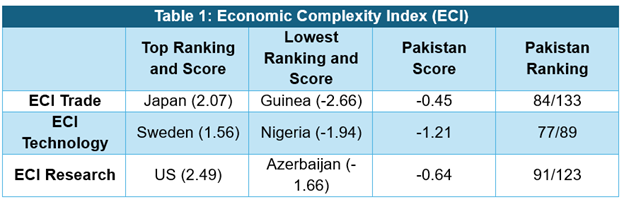

Among the top remittance-receiving countries, Pakistan has the lowest HDI (0.54) and the highest remittance-to-GDP ratio. China and Mexico, by contrast, boast high HDI scores of 0.79 and 0.78 – with remittances forming just 0.3% and 3.6% of their GDPs respectively (Figure 1). This suggests that their economies are not reliant on remittances, nor are these inflows a primary focus of their economic strategies.

The Twin Effects of Remittances:

But why isn’t Pakistan’s $30 billion remittance inflow translating into tangible gains in human development or sustained economic growth? Because the system isn’t structured to absorb it productively. Instead, the channels through which remittances are utilized in the economy are fueling Dutch Disease – driving consumption in non-tradables and weakening the export base.

As remittances increase household incomes, they boost overall consumption, particularly of non-tradable goods like food and housing. Given the short-run inelasticity of housing supply, rising real estate prices lead to demand-pull inflation. This is especially significant because housing carries the second-highest weight in the Consumer Price Index. As prices rise in the home country relative to its trading partners, the real effective exchange rate (REER) appreciates, eroding export competitiveness. Even though the central bank allows gradual PKR depreciation, persistent domestic inflation continues to appreciate the REER, thus impacting exports.

The outcome? Despite substantial financial inflows, socio-economic growth remains stagnant or negative. This reflects the classic spending effect of remittances – where increased consumption in non-tradables, rather than productive investment, predominates.

Another channel through which remittance inflows can stall growth is the resource movement effect. As non-tradables become more profitable – particularly real estate and construction – capital, labor, and investment shift away from tradable sectors like export manufacturing. This reallocation erodes industrial capacity and contracts the export base. In effect, the tradable sector is hollowed out, unable to keep pace globally.

Together, the twin forces of the spending and resource movement effects encapsulate the symptoms of Dutch Disease.

This distortion is further compounded by rising imports – driven by REER appreciation and consumption – and declining exports due to both a stronger REER and the structural shift away from tradables.

Figure 2 captures this dynamic: over the past five decades, Pakistan’s remittance-to-GDP ratio has steadily climbed, while the export-to-GDP ratio has declined. Imports, meanwhile, have grown in tandem with remittance inflows, underscoring the structural imbalances at play.

What we’re witnessing is not prosperity, but a cycle: more migration, higher remittances, increased consumption in non-tradables, rising inflation, and a weakened export base – leading to stagnating or declining economic growth.

As El Hamma (2018) noted, remittances promote growth only where strong institutions and financial systems exist. Without them, they serve as a survival tactic. The adverse impact of remittances is further supported by Acosta et al. (2009) and Chami et al. (2005), who show a negative correlation between remittances and growth. More recently, Dr. Ahmed Jamal Pirzada cautioned against the growth of remittances in Pakistan, noting that it could lead to broader economic vulnerabilities.

Impact of Remittances on Pakistan’s Export and Growth Trajectories:

To further assess whether remittance inflows drive growth in Pakistan, we ran OLS estimations to examine the impact of remittances (as a percentage of GDP) on exports to GDP, imports to GDP, consumption to GDP, and overall GDP growth. The results are summarized in Figure 3. Our estimates suggest that a one-percentage-point increase in remittances to GDP leads to a 0.67 percentage point decline in exports to GDP, a 0.23 percentage point increase in imports to GDP, a 1.209 percentage point rise in consumption, and a 0.07 percentage point decline in GDP growth.

The negative correlation of remittances with exports and GDP growth, and the positive correlation with imports and consumption comes as no surprise in our model, especially in the case of Pakistan.

As discussed, a key explanation lies in the emergence of a dependency culture. Higher remittance incomes boost overall consumption, which also increases imports. Additionally, financial inflows trigger spending and resource movement effects toward non-tradables, weakening the tradable sector and exports. Consequently, Pakistan’s over-reliance on remittances over the past 50 years has diverted resources from productive export sectors, thereby contributing toward declining economic growth.

Theoretically, even within the GDP equation Y = C + I + G + (X − M), the effect of increased remittances on growth is detrimental – especially when the marginal increase in consumption (C) is challenged by the negative marginal impact on the trade balance (X − M). Thus, while remittances may boost consumption, their adverse effect on exports and the trade balance dampens GDP growth, assuming investment (I) and government spending (G) remain constant.

We aren’t bracing for Dutch disease; we are already living through it:

For skeptics of Dutch Disease in Pakistan, the shift began decades ago when the country’s oldest and largest export-oriented composite textile unit started reinvesting and diversifying into cement, banking, insurance, power generation, hospitality, and now dairy. While power generation qualifies as backward vertical integration within the textile sector, all other investments are in non-tradables. This is a de facto sign of Dutch Disease: businesses avoiding reinvestment in tradable or export sectors due to reduced competitiveness. Today, nearly all export-oriented firms in Pakistan are following the same path.

In conclusion, while remittances may offer a short-term fix to Pakistan’s current account issues, they come at a high cost – deepening structural problems through the spending and resource movement effects.

In seeking temporary relief, Pakistan is sacrificing long-term growth, with fewer exports and deteriorating economic performance. What started as a cultural norm has now evolved into a strategic national policy. The evidence presented here underscores why this cycle must not continue, especially when sustainable sources of dollar inflow – exports and FDI – fail to show significant progress.

The debate is not how long this model can last, but whether it should.