Pakistan’s energy sector stands ensnared in inefficiencies, financial instability, and a chronic inability to implement meaningful reform.

With the combined gas and power sector circular debt now exceeding Rs 5 trillion, and electricity tariffs among the highest in the world, Pakistan’s energy sector is in despair and has severely eroded industrial sectors’ competitiveness.

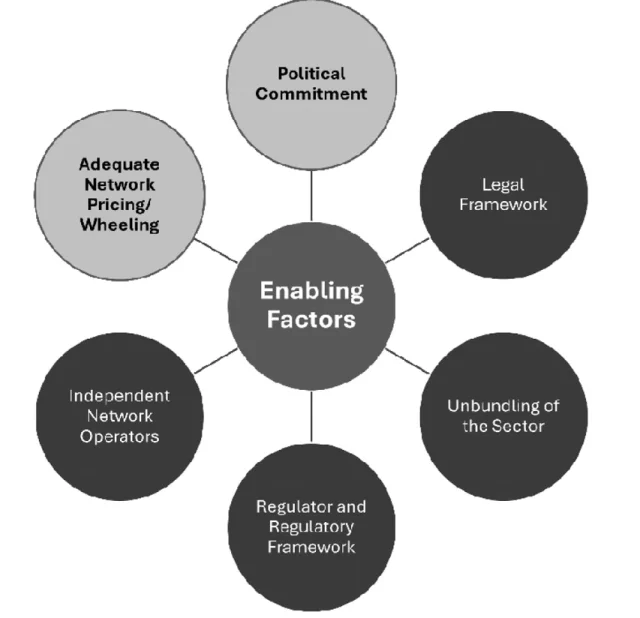

Despite decades of promises, reform initiatives like the Competitive Trading Bilateral Contracts Market (CTBCM) have exposed rather than addressed the sector’s systemic dysfunctions. Central to this failure is the absence of competitive and feasible wheeling charges for business-to-business (B2B) power contracts, a key enabler without which CTBCM or any other free-market model is bound to fail.

Indeed, the CTBCM risks being stillborn—ambitiously conceived but fatally undermined by structural flaws and poor implementation.

The CTBCM, intended as a solution to inefficiencies in Pakistan’s electricity sector, is a prime example of these challenges. Despite its promise of introducing wholesale competition, the initiative is hampered by significant obstacles that call its viability into question.

One of the CTBCM’s greatest hurdles is systemic inertia. Much of Pakistan’s power generation remains tied up in long-term contracts with excessive guaranteed returns, stifling market-driven dynamics. Without renegotiating these agreements, competition becomes an illusion.

Meanwhile, the country’s energy infrastructure is riddled with inefficiencies, theft, and excessive transmission losses. These failings inflate costs and burden the system with unsustainable circular debt. Instead of addressing these foundational issues, policymakers appear content to layer new initiatives over old problems, exacerbating rather than solving the crisis.

Currently, Pakistan operates under a single-buyer model where electricity procurement is centralized, a setup that fosters inefficiency by passing costs directly onto consumers through inflated tariffs.

The CTBCM aims to shift this model by introducing competition in the electricity market through bilateral contracts and dynamic pricing. Yet, the framework has been burdened with structural flaws, including the contentious inclusion of stranded costs and cross-subsidies in wheeling charges.

Stranded costs, the legacy financial liabilities tied to underutilized capacity, and cross-subsidies, aimed at protecting vulnerable consumers, are critical elements of the dysfunction. Their inclusion in wheeling charges has turned bulk power consumers (BPCs) into the scapegoats of a broken system. Instead of addressing the root causes of these costs through renegotiations or targeted reductions, the government has chosen to pass

them on, inflating wheeling charges to unsustainable levels.

The Discos’ and CPPA-G’s proposed Use of System Charges (UoSC), averaging Rs 27.16/kWh, are far removed from what is economically viable for industries or competitive in global markets. At 9.7 cents/kWh, the wheeling charge alone in Pakistan would be as much as twice the full power tariffs in countries like China, India, Bangladesh and Vietnam.

When challenged on the inclusion of stranded costs and cross-subsidies in wheeling charges, the Power Division entities frequently lean on the argument that these provisions are mandated by the Power Policy.

However, this justification is as unconvincing as it is shortsighted. Policies are not immutable doctrines; they are practical tools designed to evolve with shifting realities. Insisting on treating the Power Policy as a rigid, unchangeable mandate reflects a lack of political will to confront rooted interests and rethink outdated frameworks.

What’s more troubling is that the CPPA-G’s exorbitant figure raises serious questions about the bureaucracy’s commitment to reform. The proposal appears designed to perpetuate the status quo, and discourage reform rather than enable it. If the true goal were to incentivize competition and pave the way for a functional electricity market, a proposal with such prohibitive charges would never have been advanced.

Adding to these bureaucratic hurdles, bulk power consumers (BPCs) opting for wheeling arrangements would face the requirement of a one-year advance notice. This stipulation creates further disincentives for industries already grappling with high energy costs, as it forces them to bear the financial burdens of an inefficient grid for an extended period even after committing to shift. Worse still, even after exiting the grid, these consumers would be charged for recovery of stranded costs for up to five years. This extended financial obligation unfairly penalizes industries pursuing competitive alternatives.

Moreover, CTBCM must include the option of a hybrid setup—allowing consumers to draw power from both private suppliers and the grid. This would preserve grid reliability while prioritizing competitive wheeling arrangements. Such a policy can foster a more balanced energy market and help mitigate the rigidity and inefficiency currently plaguing Pakistan’s energy governance.

Another critical issue is that Pakistan’s regulatory framework lacks the resources and expertise to oversee a reform like the CTBCM.

Regulatory bodies in lower-income countries often operate with significantly fewer resources than their developed counterparts, leaving gaps in enforcement, oversight, and transparency. Poor regulation enables monopoly abuse and cartel-like behaviour among power producers, as seen in California and Turkey, where distorted markets led to inflated prices and financial losses. A stable, transparent, and fair regulatory framework is necessary to attract investment and maintain confidence in the energy sector.

Implementing the CTBCM without first strengthening regulatory institutions risks compounding existing problems. The plan calls for the creation of multiple new organizations, which could easily devolve into avenues for patronage and waste, with leadership positions awarded based on connections rather than competence. Instead of fostering competition, such a setup would exacerbate existing inefficiencies and deepen the financial strain on the energy sector.

The consequences of these policies are dire. By inflating grid tariffs and wheeling charges with stranded costs and cross-subsidies, the government has accelerated the exodus of industries from the grid to captive sources like solar power and gas/FO/coal-fired captive generation.

While this shift benefits individual enterprises, it undermines the stability and sustainability of the grid and power sector. As the pool of contributors shrinks, per-unit prices increase, pushing remaining consumers—industrial and otherwise—further into financial strain and towards more competitive alternatives.

Amid this grim outlook, recent negotiations and the termination of contracts with Independent Power Producers (IPPs) offer a glimmer of progress. These renegotiations signal a long-overdue move to rationalize the burdensome long-term agreements that have hamstrung the energy sector for decades.

Similarly, the reduction of the cross-subsidy from Rs 240 billion to an estimated Rs 75-100 billion is a notably welcome step toward alleviating the financial burden on industrial consumers. However, even at reduced levels, the cross-subsidy remains economically unviable, continuing to distort energy prices and erode the competitiveness of critical economic sectors.

To address these challenges holistically, the power sector bureaucracy must fundamentally reassess its pricing strategies. Stranded costs and cross subsidies must not be included in the wheeling charge if it is to be made financially viable for B2B power contracts.

Additionally, the one-year notice requirement for transitioning to wheeling must be revisited to foster greater flexibility and encourage broader participation in competitive energy markets, and the concept of hybrid BPCs must be allowed.

Finally, implementing a robust regulatory framework is crucial to ensuring transparency, equity, and efficiency across the energy sector, laying the groundwork for sustainable reform.

It should be crystal clear to all stakeholders involved that without market-driven and financially viable wheeling charges, the CTBCM is doomed to fail. These charges are the backbone of any functional electricity market, and their absence renders the promise of competition a hollow illusion, ensuring that the CTBCM will remain an exercise in futility rather than a pathway to meaningful reform.