By Shahid Sattar | Sarah Javaid

As carbon-intensive activities and vehicular emissions rise, so does Pakistan’s position among the world’s most polluted countries. While it is often emphasized that Pakistan contributes less than 1% to global emissions, the domestic consequences of its polluted air are nothing short of catastrophic.

The World Health Organization identifies heart disease as the leading health risk in Pakistan – yet air pollution now causes the highest number of deaths in the country.

And the scale of the crisis is reflected in recent warnings.

In 2024, UNICEF cautioned that over 11 million children under the age of five were at risk due to hazardous air quality, particularly smog. Pollution levels shattered records in Lahore and Multan, exceeding the WHO’s air quality guidelines by more than 100 times.

This alarming situation reflects a broader trend: Pakistan consistently ranks among the world’s most polluted countries, with its major cities Lahore and Karachi listed as the second and fourth most polluted major cities globally, according to the Air Quality Index (AQI).

Though environmental degradation should not be justified in the name of industrial growth, Pakistan has not even achieved meaningful industrialization.

Why, then, has air pollution reached life-threatening levels?

The answer lies in a combination of factors, including emissions from industrial operations (especially coal-fired power plants), vehicles, and the open burning of domestic waste and crop stubble. However, unless Pakistan takes urgent steps to curb rising emissions, the toxic air will continue to fuel respiratory illnesses, shorten lifespans, and make industrial cities increasingly unlivable.

So, what is air pollution?

Contrary to popular belief, it is not limited to smog alone – smog is merely one of its many forms.

According to the WHO, air pollution is the “contamination of the environment,” typically caused by various pollutants. Among the most dangerous are fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5 – tiny particles less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter that can enter deep into the lungs and bloodstream. Even at low concentrations, they pose serious health risks.

The WHO sets the safe annual limit for PM2.5 at 5 µg/m³ (micrograms per cubic meter). However, in Pakistan, the average exposure has increased to 73.7µg/m³ – over eight times the limit and far above the global average (see Figure 1).

In simple terms, Pakistan is, on average, breathing in 73.7 micrograms of fine particles in every cubic meter of air throughout the year. This is in contrast to countries like Finland (4.9 µg/m³), New Zealand (6.5 µg/m³), and Canada (6.6 µg/m³), which enjoy some of the cleanest air in the world.

While it’s evident that Pakistan’s air is far more polluted than the global average, it’s equally crucial to understand the sources driving this pollution.

Carbon-Intensive Industry, Crop Burning, and Vehicle Emissions: A Toxic Trio Suffocating Pakistan’s Air:

Pakistan’s major cities, Lahore and Karachi, are not only the most densely populated but also serve as hubs of large industrial zones, placing them at the forefront of the impact of emissions.

Evidence increasingly points to industrial activity as a major source of air pollution in these urban centers. A study conducted in Karachi identified industrial emissions as a major contributor to PM2.5 concentrations, and consequently, to the city’s toxic air (Mansha et al., 2012).

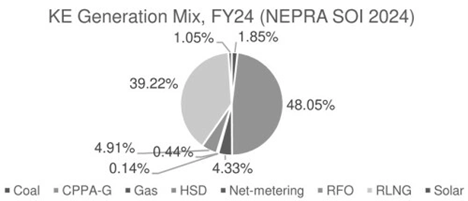

This trend has intensified in recent years. In our article CBAM, Carbon Trap, and the Impact of Irrational Gas Policies, we highlighted the rapid rise in industrial emissions, largely driven by the continued use of carbon-intensive fuels such as coal. This shift has accelerated, particularly with investments in coal-fired power plants – an expansion that multiple studies have linked to worsening air quality.

For instance, a study on the Port Qasim Coal-Fired Power Plant in Karachi estimated that in the absence of modern pollution controls, the plant’s additional PM2.5 emissions could be linked to approximately 49 excess deaths per year from stroke and heart disease (Global Development Policy Center, 2021).

Similarly, another analysis warned that Pakistan’s expanding coal-based energy production – including large-scale plants in Thar – could generate dangerously high levels of PM2.5, leading to an estimated 29,000 pollution-related deaths over 30 years (Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, 2020).

Adding to these concerns, a 2024 study near the Sahiwal coal-fired power plant found alarming concentrations of toxic metals from coal ash within a 40 km radius, highlighting the environmental footprint of these operations (Luqman et al., 2024).

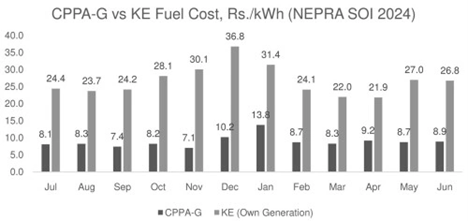

Despite this mounting evidence, policy responses remain inadequate. The government often resorts to temporary shutdowns of factories during smog season – an ineffective and economically damaging response that fails to tackle the root cause. A long-term transition to cleaner fuels like natural gas is critical yet remains overlooked in energy policy.

In addition to the emissions from coal fired plants, agricultural practices also play a substantial role in seasonal air pollution. In Punjab, air quality deteriorates every winter due to widespread burning of rice stubble – a practice adopted by farmers seeking quick and cheap field clearance for the wheat crop.

However, viable alternatives exist. India and China, for example, have promoted the use of machines like the Happy Seeder and zero-till seed drills, which allow for wheat sowing directly through crop residues – helping cut emissions and conserve soil health simultaneously.

Vehicular emissions compound the problem. Although Pakistan adopted Euro II standards in 2012, enforcement is weak, and many vehicles – especially older ones – fail to meet even these outdated norms. Meanwhile, countries have moved to Euro V and VI, improving urban air quality.

Pakistan need not reinvent the wheel. China’s example shows that sustained, coordinated action can yield results. In 2014, it launched a nationwide ‘War on Pollution,’ which included the phasing out of coal-fired boilers and industrial furnaces, as well as the conversion of coal-fired plants to gas-fired ones – eventually leading to a 32% reduction in particulate matter levels across major cities (Nakano & Yang, 2020).

In stark contrast, Pakistan’s inaction and lack of meaningful steps have led to devastating consequences from air pollution.

The Cost of Inaction: Air Pollution’s Devastating Toll on Pakistan:

Driven by carbon intensive emission, air pollution has become more harmful than any other disease. In fact, it is now the leading risk factor for death in Pakistan (Figure 2).

Several studies have linked the country’s toxic air to reduced life expectancy. The Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago reports that air pollution lowers the average lifespan by 3.8 years, and by up to 7 years in the most polluted regions. PM2.5 and smog are the main drivers of this growing health crisis.

Pakistan also ranks among the countries with the highest death rates from air pollution. With 192 deaths per 100,000 people, nearly double the global average of 104, the country is close to the top ten globally. In comparison, Finland, which has some of the cleanest air, records only 7 deaths per 100,000.

This public health crisis cannot be addressed through temporary bans and seasonal shutdowns alone. The root causes such as uncontrolled carbon emissions, polluting transportation systems, and routine crop residue burning, are well known and must be tackled through a coordinated policy action.

Cleaner energy sources, stricter enforcement of vehicle emission standards, and the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices are no longer optional. As Pakistan continues to lose lives, air pollution is not just an environmental concern – it has become a national emergency.

Addressing it will require a revamp of the energy policy and sustained political commitment. Without this, unfortunately, Pakistan will keep on suffocating – with its industries deepening their dependency on carbon and its people gasping for clean air.