Implications of the US-China Trade War – South Asia’s $8 Billion Opportunity in Value-Added Textiles Slipped Through the Cracks

By Shahid Sattar | Sarah Javaid

Six years after their imposition, the Section 301 tariffs under the U.S. Trade Act of 1974 continue to significantly impact Chinese imports, especially in the textiles and apparel sectors. Initially implemented in 2018, these tariffs targeted 5,745 products, with rates increasing to 25% and an additional 10% tariff. The tariffs were aimed at addressing intellectual property theft and other unfair trade practices, as outlined by the U.S.

In addition to the strain on the Chinese textile and apparel industries through these tariffs, the world has witnessed a shift in global textile supply chains, with U.S. GSP textile beneficiaries and alternative sourcing destinations stepping in to fill the void.

A 15% tariff was applied to imports of apparel, on top of the WTO’s Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariffs, which in 2018 averaged 14.4% for knitted apparel (HS Chapter 61) and 10.4% for woven apparel (HS Chapter 62). These tariffs were compounded by additional duties and anti-dumping measures aimed at specific Chinese companies and apparel products.

This evolving scenario prompted discussions on which countries were poised to benefit from China’s declining apparel exports to the U.S. While several contenders were expected, Pakistan emerged as one of the potential South Asian players that could benefit.

Trade War’s Toll on China’s Textile Exports to the U.S.

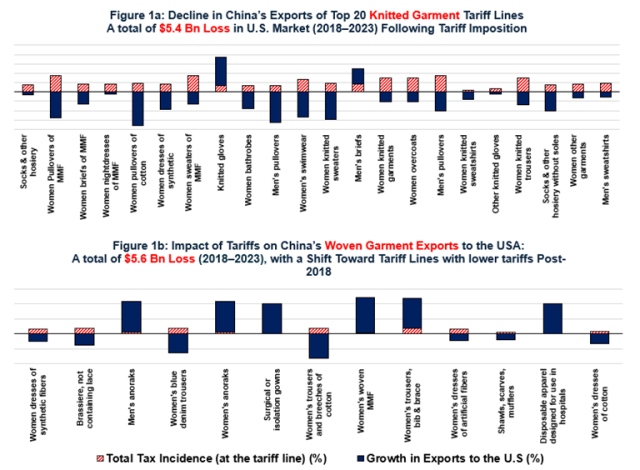

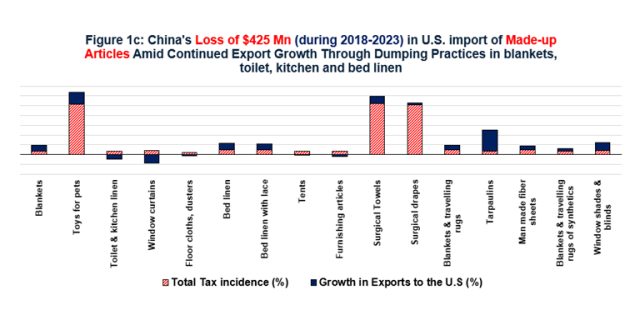

Later in 2019, the U.S. enacted the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) to counter forced labor practices in China. Combined with tariffs and legislative measures, Chinese exports to the U.S. have suffered significant losses: USD 5.4 billion in knitted garments (Figure 1a), USD 5.6 billion in woven garments (Figure 1b), and USD 425 million in home textiles (Figure 1c). Despite extremely high tariffs, China continued to export its low-cost articles, such as blankets, bed linen, toilet linen, kitchen linen, and other made-up articles under the home textiles category, with a noticeable shift towards tariff lines with comparatively lower duties.

China Plus One

Simultaneously, China’s manufacturing landscape underwent a significant transformation, driven by rising wages, stricter environmental regulations, and the adoption of digital technologies. Many Chinese companies began relocating operations to overseas destinations or shifting production to China’s western inland regions as part of the “China Plus One” strategy, aimed at diversifying supply chains and reducing dependence on China.

This shift spurred discussions about alternative manufacturing hubs for labor-intensive Chinese textile businesses, with Pakistan emerging as a potential candidate. However, the relocation of Chinese manufacturing to Pakistan was impeded by security concerns, a challenge that still remains unresolved.

One Country’s Loss Is Another Country’s Gain

Trade wars inevitably create distortions for some players while offering opportunities to others. For countries in South Asia, the US-China trade war was a significant opportunity.

As the largest single buyer of textiles and apparel, the U.S. remains a lucrative market for countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh, which rely heavily on textile and apparel exports.

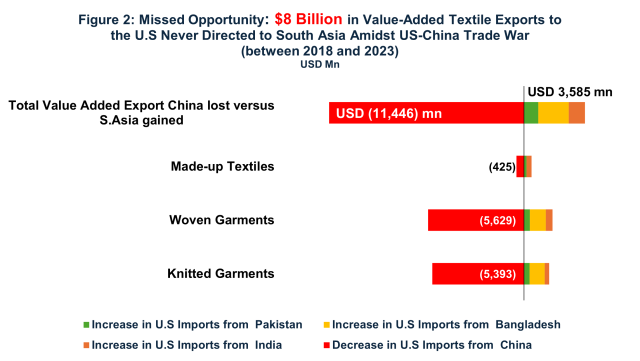

However, much of the opportunity was seized by Vietnam, Cambodia, and Mexico. Between 2018 and 2023, China’s value-added textile exports to the U.S. declined by USD 11.5 billion, but South Asia collectively exported only USD 3.6 billion to the U.S., missing an estimated USD 8 billion potential (Figure 2). Southeast Asian countries, particularly Vietnam and Cambodia, increased exports to the U.S. by USD 3.1 billion, while Mexico benefitted significantly from the shift, aided by zero tariffs under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) effective from 2020.

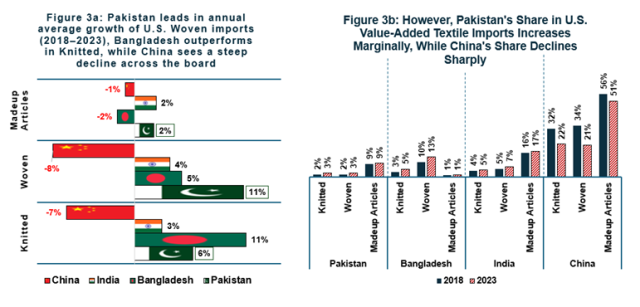

However, during this period, Pakistan achieved a notable Average Annual Growth Rate (AAGR) in U.S. imports of value-added textiles. The country led in AAGR for woven garments, with Bangladesh closely competing in knitted garments and India in the market for made-up articles (Figure 3a). A deeper analysis of South Asia’s potential to seize these opportunities lies in examining its share of the U.S. import basket. While China’s share sharply declined, South Asian economies saw minimal or stagnant growth in their share of U.S. imports of value-added textiles, highlighting a missed opportunity to capitalize on China’s diminishing export footprint (Figure 3b).

Although the USD 8 billion gap is substantial, reclaiming the lost share of China’s textile exports to the US demands a more strategic approach from countries like Pakistan.

The Role of the US GSP in Capturing China’s Lost Exports to the U.S.

All these economies, including Pakistan, once benefited from the U.S. GSP program before losing their statuses: Pakistan’s expired in 2020, Bangladesh’s was terminated in 2013 following the Rana Plaza incident, and India’s was revoked in 2019 due to insufficient market access. However, the benefits for Pakistan were minimal, with only 1.5% of its value-added textile exports to the U.S. (USD 42 million out of USD 2.9 billion in 2020) qualifying for GSP preferences.

India and Bangladesh similarly experienced limited gains, with just 0.46% and 0.7% of their value-added textile exports benefiting under GSP before their statuses were revoked. In contrast, ASEAN countries effectively took advantage of U.S. trade realignments. In 2023, ASEAN exports worth USD 11.7 billion benefited from GSP status, solidifying their position as key suppliers to the U.S. market.

South Asia’s minimal reliance on the U.S. GSP program is one of the many reasons for not fully leveraging the U.S.-China trade war. Facing tariffs of up to 16%, Pakistan’s value-added textile exports could have greatly benefited from improved access to the U.S. market, potentially capturing a larger share of U.S. imports.

Potential versus Capacity

Two major developments have reshaped global trade in value-added textiles: China’s shift away from textiles to focus on other value chains and the relocation of its textile industries due to U.S. tariffs.

Viet Nam, with its competitive labor costs, extensive trade agreements, and growing manufacturing capabilities, has long attracted Chinese investments in sectors like furniture and textiles. However, it has yet to emerge as a global manufacturing hub capable of replacing China.

When it comes to Pakistan, in 2023, the U.S. imported USD 144.4 million worth of knitted garments from Pakistan under China’s top tariff lines in the U.S. import basket, compared to USD 3 billion from China for the same tariff lines. Similarly, U.S. imports of woven garments from Pakistan totaled USD 315.5 million, significantly lower than the USD 2.6 billion sourced from China. For made-up articles, Pakistan exported USD 473.5 million to the U.S., significantly less than the USD 6.3 billion supplied by China on the same tariff lines (see Figures 1a, 1b, and 1c).

Pakistan struggles to export textiles exceeding USD 100 million per tariff line in categories where China’s exports run into billions. A major challenge is the inadequate pricing of inputs within Pakistan, which undermines the competitiveness of its exports, making them even less competitive in the face of high duties.

While these figures demonstrate Pakistan’s ability to export and compete in international markets to some extent, they also reveal the structural barriers hindering its full potential. With an estimated annual textile manufacturing capacity of USD 25 billion, Pakistan’s textile exports peaked at USD 19 billion in 2022, the best year for Pakistan’s trade economy. The USD 6 billion gap from its capacity remains, which Pakistan can unlock by addressing structural inefficiencies and embracing market-driven pricing across the value chain.

A Trump Card for Pakistan’s Exports?

Structural inefficiencies and the absence of market-driven pricing present challenges, while a downturn in global demand could worsen the situation. With Donald Trump’s return to the U.S. presidency, tariffs are set to become a key component of his economic agenda. Trump argues these tariffs will not burden the U.S. economy but shift costs to other countries, particularly China and those closely associated with it. While China has endured much of the impact, such tariffs could severely affect economies like Pakistan, where exports are already under pressure. Meanwhile, Trump’s administration is considering a flat 20% tariff on all imports as part of its broader trade strategy.

The U.S. remains Pakistan’s largest trading partner, contributing a significant trade surplus. In 2024, Pakistan exported USD 5.4 billion to the U.S., approximately 20% of its total exports, with textiles and apparel making up more than 70% of that figure. A 20% tariff could disrupt Pakistan’s manufacturing sector, especially its textile and apparel industries, which are central to its export economy. The timing is particularly challenging as Pakistani businesses are also grappling with high taxes and an energy crisis.

However, there is a potential silver lining. Trump’s tariff policy primarily targets economies benefiting from China’s relocated production, so countries like Vietnam, Cambodia, Mexico, and Canada are at greater risk. Pakistan, which does not fall into this category, may avoid these tariffs. Bangladesh’s new government, focused on strengthening trade ties with both China and the U.S., may face foreign policy dilemmas. Alternatively, Trump’s plans to renegotiate the USMCA could completely shift attention away from South Asia.

For Pakistan, effective economic diplomacy is essential to expanding its export footprint in the U.S. market. The pressing question remains: how should Pakistan strategize its diplomacy to strengthen its trade position amid these global shifts?

Charting a way forward

To secure its position in the U.S. market, Pakistan must actively pursue the revival of GSP status by negotiating its renewal and advocating for revised tariff lines to secure duty-free or reduced-duty access. Such access is essential in the ongoing tariff war.

Pakistan’s products in the U.S. market primarily cater to low- to middle-income groups. Additional tariffs would make Pakistani products less competitive, ultimately reducing demand for Pakistani apparel in the U.S.

With that, Pakistan is the second-largest destination for U.S. long-staple raw cotton after China. In 2023, Pakistan imported over USD 379 million worth of U.S. cotton, primarily for clothing and blanket manufacturing. Cotton imports were even higher in 2022, reaching USD 615 million. As domestic cotton production fails to meet demand, the U.S. remains a crucial supplier, with its raw cotton entering Pakistan duty-free. This contrasts sharply with the high tariffs, up to 16% imposed on Pakistan’s value-added textiles exported to the U.S.

With declining domestic crop production, Pakistan’s reliance on imported cotton is expected to grow. Under the Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA), apparel assembled in the Caribbean and Central America using U.S.-origin fabrics, yarns, and threads enters the U.S. duty-free. However, raw cotton falls outside the CBTPA’s scope and is governed by general trade agreements.

The window of opportunity created by the U.S.-China trade war may be closing, and it is uncertain whether the U.S. will continue favoring South Asian textile and apparel industries. However, Pakistan still has room to maneuver. Economic diplomacy will be critical in advocating for Pakistan’s interests in the U.S. market. The real challenge lies in addressing internal structural issues that hinder export growth, which deserves immediate attention from the decision-makers.

To begin with, it is extremely urgent for Pakistani authorities to negotiate a trade agreement with the U.S. to secure duty-free or reduced-duty access for value-added textiles assembled in Pakistan using U.S.-origin cotton, before the opportunity slips through the cracks again.